Houston Zoo Chief Veterinarian Helps Restore Giant Tortoise Population in Galapagos

Written by Dr. Joe Flanagan, Chief Veterinarian at the Houston Zoo

The Giant Tortoise Restoration Initiative is a long-term plan to restore giant tortoises in Galapagos to their original populations and densities. In November 2015, I participated in one of the most ambitious projects yet to recover species. In an accident of human history, giant tortoises originally intended to be food on long ocean voyages, landed on the west coast of Isabela Island where they established a small colony, adjacent to the “native” tortoises of Wolf Volcano, the northernmost volcano of Isabela Island.

Genetics done by Yale University scientists show that these unique animals are remnants of 2 populations of tortoises now thought to be extinct. The Pinta Island tortoise went officially extinct in 2012 with the passing of “Lonesome George”, but the population was depleted nearly 100 years ago. The Floreana Island tortoise went extinct in about 1850, shortly after the island was visited by Charles Darwin.

32 Animals were brought into captivity to form the breeding nucleus that will hopefully restore giant tortoises where none have roamed for as much as 200 years! I was invited to treat the tortoises for ectoparasites (ticks) and endoparasites (worms) to prevent these from becoming problems for the breeding population at the rearing center on Santa Cruz Island.

As a zoo veterinarian for over 30 years, I know that moving an animal to a new home is one of the most stressful things that can happen to it. Moves from zoo to zoo can bring out disease symptoms from otherwise unapparent bacteria, viruses, or parasites. Moves from the wild to captivity are even more likely to create problems — with a change in diet, a new social environment, and a need to learn to navigate new habitat, which includes people. To help animals in this transition, we treat them for both internal and external parasites — such as ticks — to reduce the load.

Ticks. Nasty, skin-crawling, blood-sucking, head-burying, disease-transmitting ticks. I hate them. Wild giant tortoises in Galapagos are frequently infested with dozens or even hundreds of ticks attached to their skin and even to their shells! I was fortunate to participate in the 2008 tortoise census on Wolf Volcano, and on that trip we encountered ticks on most of the hundreds of tortoises observed, as well as along tortoise trails. For the 2015 expedition, it was my job to get rid of as many of these nasty creatures as I could from the tortoises headed to the Tortoise Center on Santa Cruz.

While ticks are “normal” on giant tortoises in Galapagos — part of the process of natural selection, as are the diseases they might carry — they are problematic for captive animals and the people who care for them.

As for internal parasites, the primary ones affecting tortoises are worms. Like their external counterparts, there is a balance between the worm load and the tortoise, with wild tortoises regularly exposed to low levels. Some think the presence of intestinal parasites may help tortoise digestion. When a tortoise is stressed, however, a heavy population of worms can further weaken it. Although it is nearly impossible to eliminate all worms from the tortoises, by reducing the burden, the tortoises have a better chance of adapting to captivity.

During the planning phase of the 2015 Wolf Expedition, I worked closely with GC’s Wacho Tapia to develop a treatment protocol for tortoises moving to the Tortoise Center on Santa Cruz and to ensure we had all the necessary supplies. After each tortoise was carefully delivered onto the deck of theSierra Negra and freed from the net, we did a brief physical examination, took standard measurements, made sure each animal had a microchip for identification, collected a blood sample to verify genetics, and — in some animals — to look for tick-born disease.

Before placing the tortoise into the ship’s hold, it was sprayed with a tortoise-safe insecticide and treated orally with a de-wormer, effective against the most-probable worms. Our goal was to improve the health of each tortoise, prevent “seeding” the corrals at the Tortoise Center with ticks and tortoise parasites, and, in consideration for the crew of the Sierra Negra, make sure the ship didn’t get infested with ticks!

As described in previous blogs in this series, locating tortoises on Wolf was slow until it rained on the third day. Rain brings tortoises “out of the bush.” The dispersed teams started to find tortoises, sometimes in very high numbers! Native Wolf tortoises are a large, dome-shaped species, which still occurs in high numbers due to the inaccessibility of their habitat precluding much harvest by whalers and other seafarers in centuries past. Although majestic and fascinating, these tortoises were not the objective of our mission so they were only counted and measured, then left to live their lives in one of the most unspoiled habitats in the world.

But when a few of the teams started encountering tortoises “of interest” — animals previously identified by the Yale team as genetically significant or with the characteristic saddleback shape of those animals — we found ourselves scrambling, with tortoises arriving two or three at a time; sometimes with up to six giants wandering the deck before we could examine them.

Near the end of the expedition, we worried we’d run out of space to house all the animals that were coming in! The ship’s hold was full. We started lining the gunnels with larger animals that were “misbehaving” in the ship’s hold — climbing over their brethren, and knocking over what we thought was safely stowed gear. We ultimately collected 32 animals to form the breeding nucleus to resurrect two species of tortoises and to restore ecological balance to Floreana and Pinta Islands.

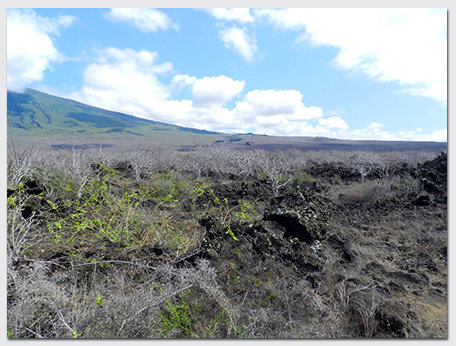

While my main “job” on this expedition concerned tortoise health and prophylactic treatment for potential disease organisms, I also joined the team that searched a patch of Wolf Volcano’s lower slopes for tortoises, going ashore each morning. Our zone was a patchwork of a’a lava, broken plates of pahoehoe lava, and fine soil, with vegetation ranging from completely barren to thick, impenetrable stands of woody vegetation. At this low elevation, we encountered few adult tortoises; most animals we found measured 6-18 inches in length. It is hard to believe that tortoises could survive in such a harsh environment, without anything green to eat and no source of water to drink. We humans left bits of skin and blood as we walked over the rough terrain and through thick and thorny vegetation.

Each afternoon, we returned to the ship to receive and process tortoises. After the call-ins from the field teams, the helicopter made several trips to collect the tortoises. We’d watch its return against the backdrop of Wolf’s green slopes, trailing a net full of tortoises.

It’s hard to describe the feeling of being part of a conservation effort of this magnitude. For more than 20 years I’ve been lucky to visit these remote islands and work with their unique species, volunteering on numerous projects with myriad organizations. Over the years, I have witnessed many positive changes: invasive species have been eliminated on some islands; populations of some native and endemic species are recovering; and every year more of Galapagos is protected and restored to its primordial condition.

But these projects are costly. Funding for this expedition came from the government of Ecuador, Galapagos Conservancy, and Yale University, as well as out of the pockets of the expedition’s participants (many who donated their time). This high level of collaboration allowed funding from Galapagos Conservancy to be leveraged, resulting in a project many times larger than could be done by any one organization.

One of the greatest rewards of working in Galapagos is the great mix of people. The 2015 Wolf Expedition included participants from four continents — biologists, botanists, veterinarians, geneticists, technicians, park rangers, geologists, mariners, and pilots. Getting to know each other as we focused on our mission — talking, dining, traveling, and working together — a synergy occurred. New questions formed; some were captured for further consideration for future research projects; others were resolved or discounted. All resulted in friendships and collaborations that will last a lifetime. The conservation of one of the world’s greatest treasures is a unifying force. Galapagos is a magic place.

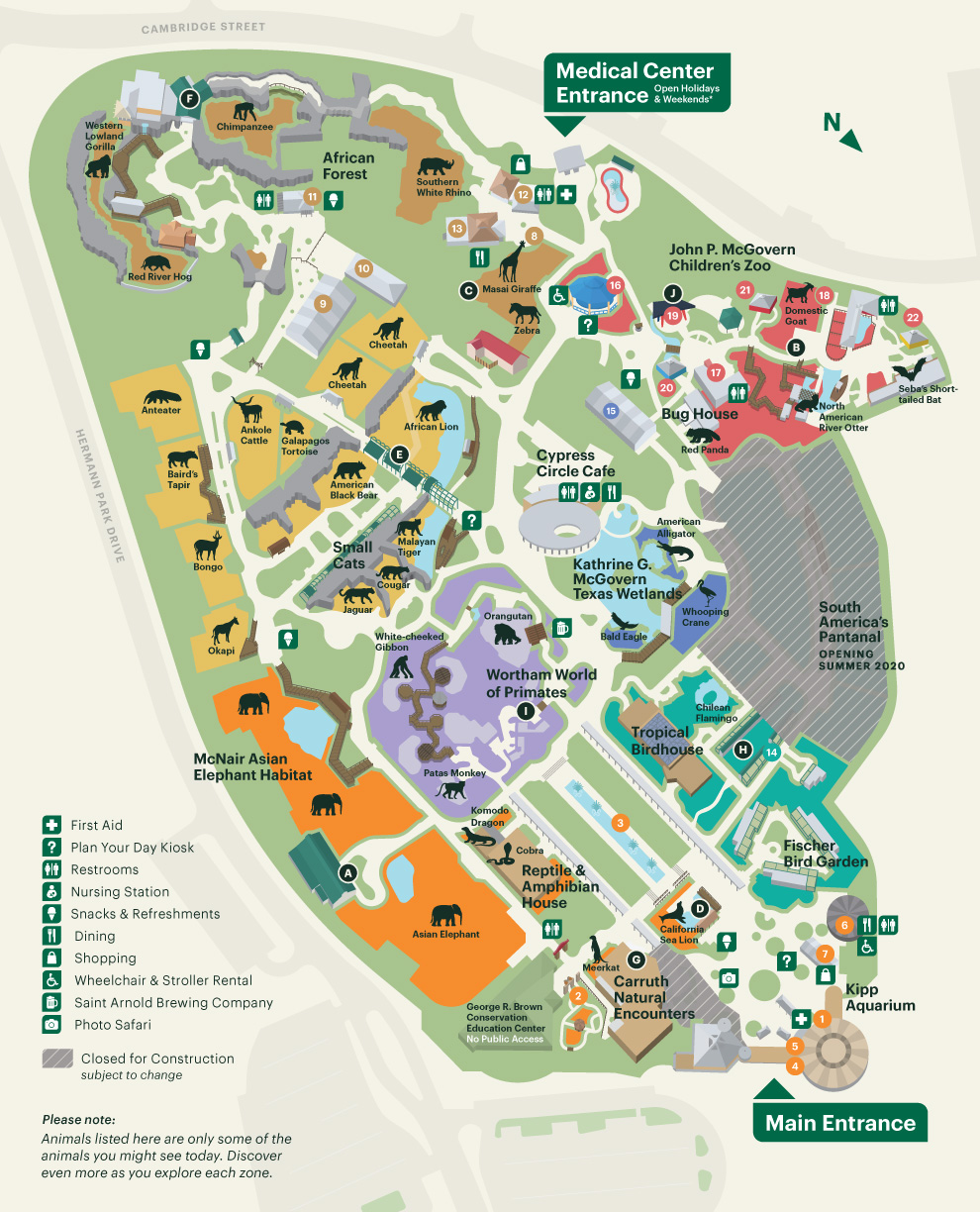

To read more about this historical expedition, please visit the Galapagos Conservancy blog here. You can also visit the Zoo’s Galapagos tortoises near Duck Lake. Every time you visit the Houston Zoo, you help save animals (like giant tortoises) in the wild!